All products and services, “things”, work in their particular way by design. No thing magically evolves in a vacuum. Any product exists because someone made it so.

Design is a conscious process of addressing people’s needs with meaningful solutions. It can be viewed from many angles, including accessibility, usability, experience and service. Considering these aspects in a thoughtful and responsible manner leads to products that are better for the planet, people and profit.

User versus client

In design terms, a user is a person who interacts with the solution, such as product interface or a service touch point. While this might seem obvious, there’s an important nuance to it. A user can be practically anyone – of any gender, age, demographic, ability and situation. A user is not always the same person as a customer or a buyer, and they might have different needs and expectations.

Imagine a point of care technology. While a medical solution might be purchased by a hospital procurement manager, the end user is likely a healthcare worker. Specifically, the end user might be a nurse or doctor under stress, using gloves or interacting with the tech during a power outage. This is vastly different from the calm meeting room, where demos and buying decisions are typically made.

Making things accessible and usable

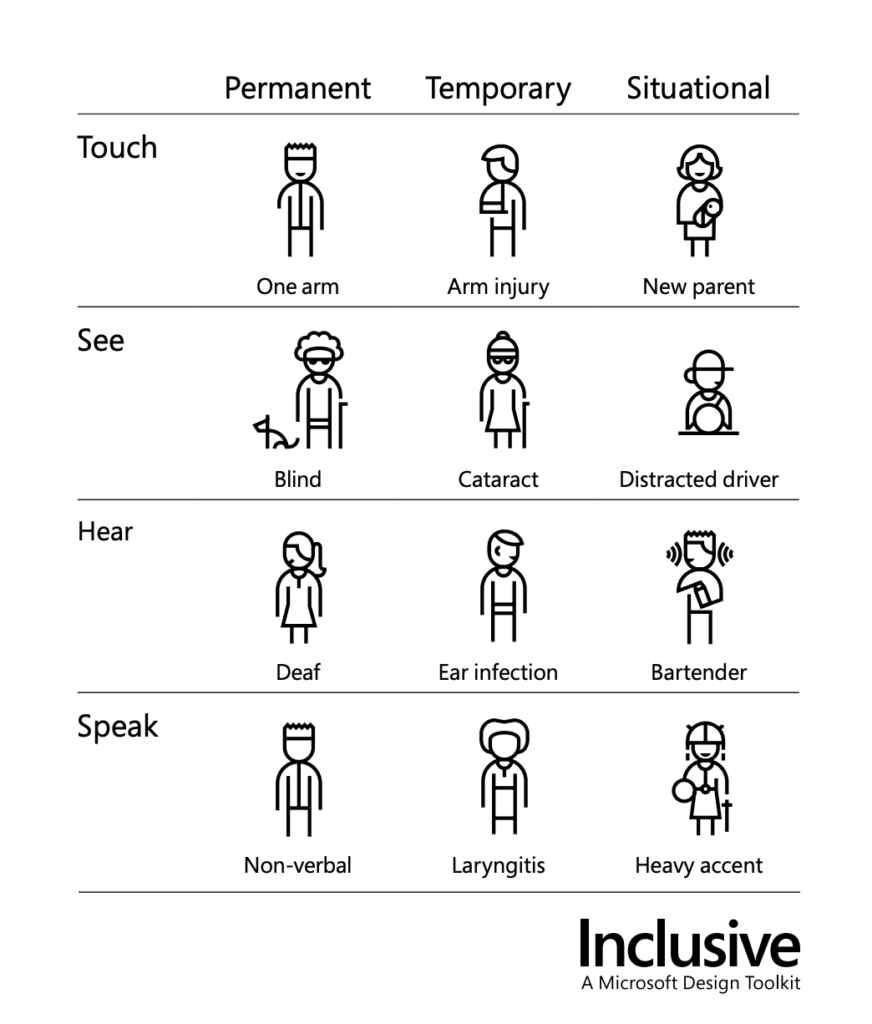

If you ever used a ramp, a keyboard shortcut or subtitles, you too have benefited from accessible design. Accessibility aims to serve people with permanent, temporary and situational disabilities, resulting in inclusive products that also often benefit a wide audience.

The Persona Spectrum. A diagram of permanent, temporary and situational disabilities for touch, see, hear and speak. Image: Microsoft Design Toolkit. (CC BY-NC-ND).

Usability, in turn, describes how well the thing functions in general, such as:

- Can users figure out what the thing is and what it is doing right now?

- How easily can users learn to use it?

- How efficiently can users perform tasks?

- How well are users equipped to cope with errors?

- How fast can users re-establish proficiency after a while?

Consider a heart rate monitor, for example. How would its design cater to clinical staff versus self-measuring patients at home? Or field hospitals versus palliative care? Seeing a correct heart rate unites all of these use cases. Solutions on how to retrieve such a metric, at what precision, and with what sort of analysis and alerts, likely vary.

Access and usability lay the ground for the product’s core function. After all, products are limited to their predetermined features and can only adapt through new versions or updates. Accessibility and usability as an afterthought can become very expensive. Fixing the product creates extra costs – so does handling recalls, reclamations and reputational damages.

Making things useful, attractive and enjoyable

The existence of ramps, keyboard shortcuts, subtitles and other accommodating technologies connects to access and usability. How well these things work, and how delightful they are to use, expands to user experience.

Good user experience creates a balance between functional, emotional and aesthetic needs. Products that are usable, useful and enjoyable tend to have loyal customers and demand.

An important note about terminology: there is no way to design user experience.

A product cannot instil itself into every user’s mind and force them to feel in a same, certain way. Each individual experience is unique, changes over time and encompasses all aspects of interaction. However, products can be designed towards their intended interactions and experiences.

Take heart rate self-monitoring at home, for example. A usable device allows non-medical users to measure heart rate on their own, regardless of their varying abilities. A useful monitor signals abnormalities, in addition to showing results. And an enjoyable device, in a relative sense, would do so calmly and with clear follow-up options, ideally guiding towards relevant and timely medical support.

A paramedic measuring heart rate on an unconscious patient, on the other hand, might not find the above attributes as attractive. Instead of calm alerts and guides, a medically trained user may prefer efficiency and real-time data for several vital signs – even if it leads to a more complex interface.

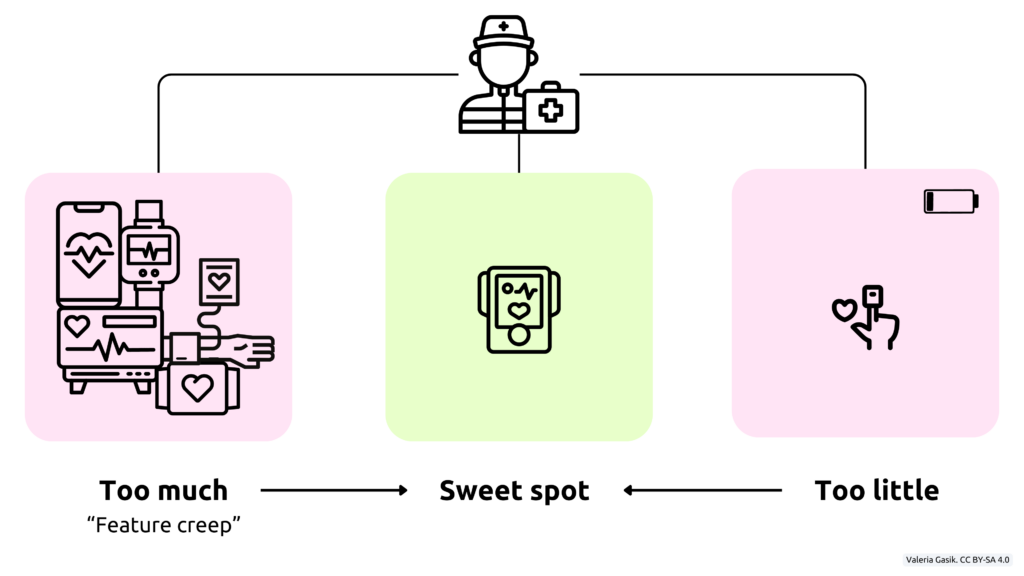

Designing for an ideal experience is a puzzle. It is not about making ready things pretty nor “sprinkling” experience intentions on top with glossy promotion. Instead, it’s a process of discovering user needs and figuring out the most optimal solutions. A great design finds a sweet spot between attempting to cater to everyone and overfocusing on a narrow use case.

A great design responds to user needs. Image: Valeria Gasik. (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Making things part of the service

A ramp with a gentle slope, wide width and edge protection isn’t serving its users well, if it leads to a narrow, heavy door with a threshold.

Service design considers how “a thing” fits into a bigger picture. Depending on the task at hand, the bigger picture might focus on the organisational level – such as its people, products, services and partners, or a higher, systemic level – connected environment, communities and practices.

Any product and service exist in space and time.

A user interacting with a heart rate monitor does that for a reason. Something happened before the measures were taken, and something will happen after. Often, other people are involved, like a nurse monitoring a patient, or a personal trainer, following the client’s heart rate during cardio.

Even when the heart rate measuring is done by an individual without external triggers, there’s still a connection to their life. What prompted a person to look at their heart rate? Why now? Why in this way?

Thinking how a thing fits into the world can get overwhelming. That’s where approaches, such as customer journeys, interaction touch points, service blueprints and stakeholder maps come in handy. Such methods, when used mindfully, help to narrow down to the relevant framing and to prioritise who needs what and why.

Continuous discovery

Thinking about design in a holistic way elevates business.

Zooming in and out from specific expectations and interactions to broader context and environment inspires us to think about what is really missing. There’s enough useless one-off gadgets, apps and trinkets polluting the world. There’s also still plenty of needs and pains worth addressing in a sustainable manner.

Useful, usable and enjoyable things create demand and stand against competition over time. Well-designed products and services are economical, as they need less fixing, less maintenance and less support. Continuing to discover what people need and how solutions may cater such needs in an optimal way, while respecting planetary boundaries, leads to sustainable and impactful businesses.